Rabbi Moshe Yitzchak Ashkenazi (Tedeschi) (1821 - 1898) was an Italian Rabbi & Bible commentator in 19th century Italy. This post (the first in a planned series of posts) will explore and translate his autobiography, which he published as an addendum to his book of sermons Simchas HaRegel.

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

Rabbi Moshe Yitzchak Ashkenazi (Moisé Tedeschi) was born in 1821 in the city of Trieste, Italy.

A student of Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Zalman (1807 - 1885), and Rabbi Shabsai Elchanan Trevis (see introduction to Hoil Moshe, Nevi’im Rishonim), he was also heavily influenced by and considered himself to be a student of Shadal (Shmuel Dovid Luzzatto, 1800 - 1865). Rabbi Ashkenazi lived in Trieste and taught in the local Talmud Torah school for most of his life. He also temporarily served as Rabbi of Trieste for a short time, as well as Rabbi of Split, Croatia before returning to Trieste.

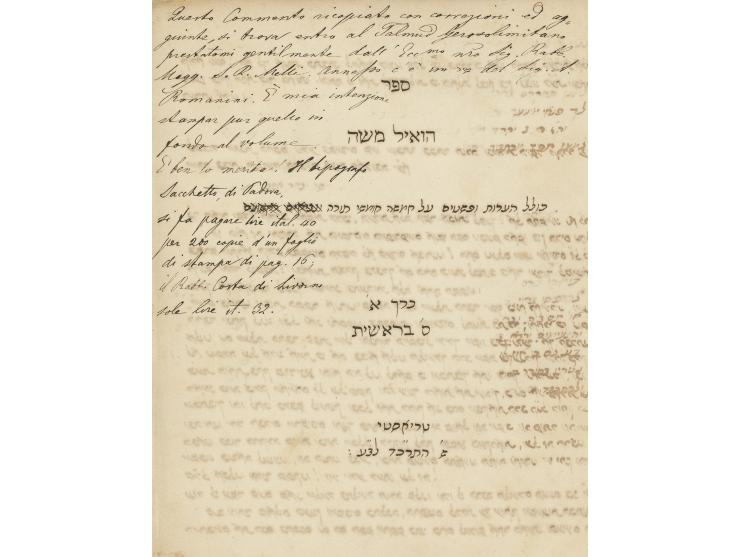

Rabbi Ashkenazi followed in his teachers footsteps and worked for many years on producing a Torah commentary, with his magnum opus being a commentary on all 24 books of the Bible titled Ho’il Moshe. Ashkenazi also wrote an ethical book titled, Mussar Melachim and a slim book of sermons for the holidays Simchas HaRegel. It is to this last book that we turn our attention.

(Autograph page of Ho’il Moshe)

NEW EDITION

Two years ago, I opened up the daily email from Girsa Seforim store in Yeushalayim with new Seforim. Girsa sends an email daily and includes a written list plus sample pictures. On this day, amongst other items, three new interesting works caught my eye: 1. A new edition of Sefer Mussar Melachim from Rav Yeshaya Romanin (d. 1765), a student of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato (Ramchal) in Padua;

2. Sefer Mussar Melachim of Rav Moshe Yitzchak Ashkenazi;

and 3. Sefer Simchas HaRegel of Rav Moshe Yitzchak Ashkenazi.

I was familiar with Mussar Melachim of Romanin as I had recently purchased a copy from an auction the year prior. But I wasn’t super familiar with Ashkenazi at the time, but, as a fan of Shadal I had come across this student of his a few times and had even utilized the “print-your-own-Sefer” option for some of his volumes on Nach off of HebrewBooks. I thought these titles would be of interest to me as I am an avid connoisseur of Itlian Seforim, and so I sent R’ Aharon Biegeleisen a message asking him to set these books aside for me when they came in.

Once I received the books I saw that they were fairly straightforward and as described: Mussar Melachim seemed to be a simple ethical work, while Simchas HaRegel was a small volume of some sermons on moadim. Simple enough right?

However, once I began to read the editor/publishers introduction I noticed a small section devoted to the biography of Ashkenazi. Toward the beginning of this biography, the editor noted that this information came from Ashkenazi’s autobiography included in Simchas HaRegel, yet, when I turned to look in the new edition there was no autobiography. Furthermore, as I read the bio from the editor, I noticed that there was no mention of Shadal— while his relationship with Shadal is fairly well known (by those that heard of Ashkenazi).

Intrigued, I went to HebrewBooks.org to find a scan of the original edition of Simchas HaRegel. (published in Przemyśl, 1886). As I began to read the autobiography I realized right away what happened: Rabbi Ashkenazi quotes Shadal, an unpardonable sin in the eyes of some. This then meant one thing: Censorship à la the Prof. Marc Shapiro kind. Someone clearly didn’t want readers knowing that Ashekenazi was a disciple of the famous Italian “maskil” Shadal.

Some further comparison with the 1st edition of Simchas HaRegel showed how the autobiographical essay wasn’t the only thing removed from the new edition. In the original edition, at the end of the work and prior to the autobiographical essay Ashkenazi included a section titled Haaros Al Targum Sefer Mishlei which he introduced with a subtitle saying, “When I began to write my introduction to Ho’il Moshe on Mishlei I wrote in the name of Shadal thusly:…” The censoring of this section also underscores the issue that editor of the new edition has with references to Shadal.

However, what struck me as odd (and still does) is why someone would even want to republish works from a student of Shadal (who calls Shadal “the light of our generation” multiple times), whose own outlook and commentarial style reflect in large part those of Shadal, and then expunge all record of the connection. Why even reprint the books? I don’t have a ready explanation to this, but my research did lead me to read Ashekanzi’s autobiographical essay, and I found it to be a very worthwhile read.

As someone fascinated with Italian Jewry, and autobiographies in general being a lens into a world that was, I thought it would be worth translating the autobiography into English and sharing it with readers. The autobiography is replete with stories, anecdotes and is overall a wonderful read. Also, Rabbi Ashkenazi mentions in his autobiography that he did not merit having children, and so it is hoped that these posts, and the Torah study they should generate, will be a zechus for his neshamah.

As the translation is a careful process that requires time and effort, I am posting here the first page of the autobiography, with plans for posting the rest of it in installments over the coming weeks for the paying subscribers to this substack. My thanks to Rabbi Moshe Maimon of Jackson, NJ for his expert help in preparing this translation.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY:

Part I:

Our family name [Ashkenazi or Tedeschi, plural for Tedesco; Italian for ‘German’] demonstrates that we came from the land of Ashkenaz (Germany) to dwell in the land of the south (i.e the Ottoman empire). Similarly, our blondhair and saphire-blue eyes [NW: distinctly Germanic features] also belie our northern origin, whereas our noses and other facial features bear witness of our Jewish ancestry.

My grandfather was in charge of the household in the palace of the Sultan, Selim III (1761 - 1808), in the city of Constantinople, until the other nobles became jealous and began to spreading libelous rumors about him, forcing him to flee the capital. He thereupon traveled by foot throughout the entire land of Turkey, eventually settling in the city of Split in Croatia.

After many years in Split, he fell victim to a plague and he was quarantined out of the city. His son, Yitzchak, deeply saddened to see his father abandoned so, feigned illness to the point where he too was brought out of the city and laid next to his father. He thus managed to tend to his father in his final moments, and was present at the old man’s death, whereupon he dug a grave and then performed the ritual cleansing. After burying his father’s body, he left the the quarantine zone and returned home in peace.

Another one of my uncles, by the name of Yom Tov, was forced into exile from Croatia after the following incident. It happened once that the non-Jews in Split ganged up on the local Jews and inflicted wanton destruction on them. Some time later, my uncle Yom Tov was in a caffè when he heard one of the non-Jews wave his hands and boast, “these hands came down on the backs of the Jew; beating and maiming quite a few!” Hearing this, my uncle went outside and waited in ambush for the non-Jew to leave the store, whereupon he cut off both hands [of the non-Jew] and he ran away, never disclosing his location after that.

Another one of my uncles was named Abraham. On the day of his wedding, while standing under the wedding canopy with his bride, he said something that his father did not feel was appropriate. My grandfather slapped his son, the groom, on his cheek in front of the entire crowd! My uncle demonstrated great fortitude, and he grasped his father’s hand and kissed it in a public display of contrition.

My father came to settle in Trieste [Italy]. During a visit to nearby Gorizia, where he stayed once at the local inn, he beheld my mother and heard her sweet voice. He was quiet taken with her, and then and there chose her for a wife. My mother, from the family of Yosef Pincherle, was a very beautiful woman and was as well as a devoted wife. Her name was Bilhah.

Afterwards, my uncle Yitzchak also came to live in Trieste with his wife Mazal-Tov, from the family Gentilomo. These two women [Bilhah & Mazal-Tov] lived harmoniously in the same house, and loved each other like sisters.

It happened once that Rabbi Yaakov Pardo [son of the famous Rabbi David Pardo, author of Chasdei David] came to Trieste with his son David (who would later become the Rabbi in the city of Verona, Italy) to find signatories [i.e. pre-subscribers] for his Sefer Minchas Aharon. My family gave them lodgings in their home, as was their custom to extend their hospitality to all guests—particularly Torah scholars.

One day, as they were sitting around the table, a glass was brought to the table filled with brandy (Slivovitz) from which each was given a little to drink [a shot]. Rav Yaakov took a sip but he could not handle the strong taste, and so he reached for his cup of water to cool his palate. However, he mistakenly grabbed the glass filled with brandy and quaffed the entire drink. This caused him to become gravely ill, and close to death at that. My mother and aunt tended to him devotedly in his sick bed until he recovered by the grace of God and he was able to return to his hometown of Ragusa [modern day Dubrovnik, Croatia]. Thereafter, when he published his work [Minchas Aharon], he acknowledged in his introduction the kindness showed him by these two valorous women , and he thanks them for it.

To be continued…

The intros to seforim are an untapped treasure for history and understanding who these rabbanim were. The translation flows very smoothly. The problem with e the censorship that happens is that it hides the what has influenced someone.